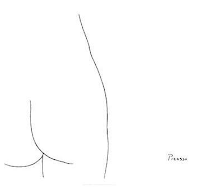

To artists, a line is a powerful geometric entity, whether it’s a straight or curved mark on a piece of paper. According to the author on neurobiology Carl Schoonover, the drawing by Picasso at left shows that we can distinguish shapes easily with a few lines, which he says “taps into our visual system's predilection for line.”

To artists, a line is a powerful geometric entity, whether it’s a straight or curved mark on a piece of paper. According to the author on neurobiology Carl Schoonover, the drawing by Picasso at left shows that we can distinguish shapes easily with a few lines, which he says “taps into our visual system's predilection for line.”Yesterday I started to pose a few questions: Are lines merely abstract constructions—artificial conventions—that we have invented to represent nature? Do they have counterparts in the real world and in our minds? Do they reflect something basic going on in our brain when we look at the world?

These can be sensitive questions for artists who do most of their work in line. They are often made to feel that what they do is just a preliminary step, or that it isn’t as advanced as what a painter does. In fact, the management of line is one of the most sophisticated skills an artist can master, and it corresponds to some of the most basic and powerful experiences of visual perception.

We use lines to describe several things:

1. A boundary of a form (B, above).

2. An edge of a surface marking (A).

3. A plane change within a form (C).

4. Or an edge of a cast shadow (D).

5. Also, a line can describe a thin form, like a tree branch or a piece of spaghetti.

A shape boundary can be regarded as a type of line. Some images, like this poster by Maxfield Parrish, can be made up entirely of overlapping shapes.

At the initial level of visual processing, neuron groups in the visual cortex begin to process shape boundaries in a similar way that they process outlines drawn on white paper. But as we'll see in later posts, edge detection is just one preliminary step in object recognition. The brain constructs an understanding of shape and form and space by combining information from many different cues.

Our visual system has no trouble sorting out boundaries, surface marks, plane changes, and cast shadows (click to enlarge). But they are not trivial tasks when you’re trying to educate a computer, even a smart computer, to see. Edge detection and feature extraction are exciting frontiers for people at the intersection of computer science and visual perception.

----

That last photo is from Wikipedia on Edge Detection

Colored cube is from GurneyJourney "Color Constancy Illusion" post.

Lines and the Brain Series,

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

Part 4

13 comments:

I don't know, I think I tend to see shapes/blocks of colour rather than lines. Though the GalaxyZoo.org project took advantage of the human ability to recognize stars versus other stellar objects and have processed an amazing amount of data in a fraction of the time it would have taken using traditional methods.

I have a question for you! I'm getting a tattoo of one of Tony DiTerlizzi's mermaids from the last book of Beyond the Spiderwick Chronicles and I want to use some of the creatures from The World Beneath. It's going to be a collage of sea creatures from a bunch of books I love. I wanted to make sure you were ok with it first! I will of course send you a picture of the finished piece. :)

Hey James this is totally unrelated to this post but I just need to say i just got my copy of Color and Light and it is one of the best books ever. Thank You!

I have really struggled with the difference between line and shape. Much more than one would think for a person who has painted and drawn for a lifetime. So the idea that the brain processes shapes and lines differently is very real to me. But the difference largely remains a mystery.

As always, very thought provoking ideas.

This sounds suspiciously like a re-incarnation of disegno vs. colore.

The 'lines do not exist in nature' statement may have use as a guide in art, but it implies a restrictive definition of the term 'line'. I see lines in nature all the time.

Thanks for your great blog, and books, James.

Reducing things to purely "line" is a much greater degree of abstraction than creating shapes as the painter usually does. In my mind, this makes a "line drawing" the most difficult artistic task to do well. While I can think of hundreds of great paintings, the number of great line drawings in art seems far less. Abstracting something to the minimal amount of information is a great skill!

Your final image of the girl and the computer generated line image perfectly illustrate how handling line is such a great skill. If you import the line image into photoshop and invert, you get a decent linear interpretation of the photograph. However it's rather confusing because no decisions have been regarding what to emphasise with the linework, what to leave out, or where the focus of our attention should be.

Any artist even using a rapidiograph pen would have unwittingly made those decisions and created an image that projects some of their personality and style.

Line seems to be a universally understood form of abstract art. It's been used since the earliest cave drawings and its use with flourish and skill still seem to be able to move something in us.

Thanks for the post

Your final image of the girl and the computer generated line image perfectly illustrate how handling line is such a great skill. If you import the line image into photoshop and invert, you get a decent linear interpretation of the photograph. However it's rather confusing because no decisions have been regarding what to emphasise with the linework, what to leave out, or where the focus of our attention should be.

Any artist even using a rapidiograph pen would have unwittingly made those decisions and created an image that projects some of their personality and style.

Line seems to be a universally understood form of abstract art. It's been used since the earliest cave drawings and its use with flourish and skill still seem to be able to move something in us.

Thanks for the post

Twilight Cat, A tattoo? Awesome, I'd be honored. Yes, please send a photo when you're done.

David, thanks for the kind words, and I'm glad you enjoy the book.

Etc, It probably is a rehash of stuff we've all thought about before, but that's what most of art learning is from my experience--just relearning the same principles.

Chris, I think the ultimate point of all this is that lines are very real to the brain, and that's what matters most when we do art.

Brad, I agree. By the way, Brad is a painter and comic artist who does a great blog (with lots of video) called "Thick Paint."

Don, I agree. Abstracting is both the simplest and the most difficult task.

Roger, I had the same reaction to that computer-generated line analysis. It couldn't see the forest for the trees. It will be interesting to see how this field of machine vision develops.

> the drawing by Picasso at left >shows that we can distinguish shapes >easily with a few lines, which he >says “taps into our visual system's >predilection for line.”

Jim, I think you meant to say that the Picasso drawing taps into our visual system's predilection for butts :)

Oh, that Pablo!!... Always trying to take credit and make trouble. The 'visual system for butts' has been well documented by anthropologists for years, its called the 'T & A' center (especially sensitive in teenagers and old-farts).-RQ

Paraphrasing another commenter in a recent post:

The question shouldn't be whether lines are real or not, but why students tend (no matter how much you push them in other directions) to use said lines to draw butts! :)

Wonderful post, thank you for sharing!

Post a Comment